The advantage of a minimally invasive approach is the ability to carefully assess the peritoneal cavity prior to resection with minimal trauma to the body. We will spend a few minutes examining the liver, omentum, and abdominal wall prior to resection. Any suspicious lesions are biopsied and sent for frozen sections. This prevents futile resections in those with unsuspected metastatic disease.

Laparoscopic Steps

Laparoscopic Steps

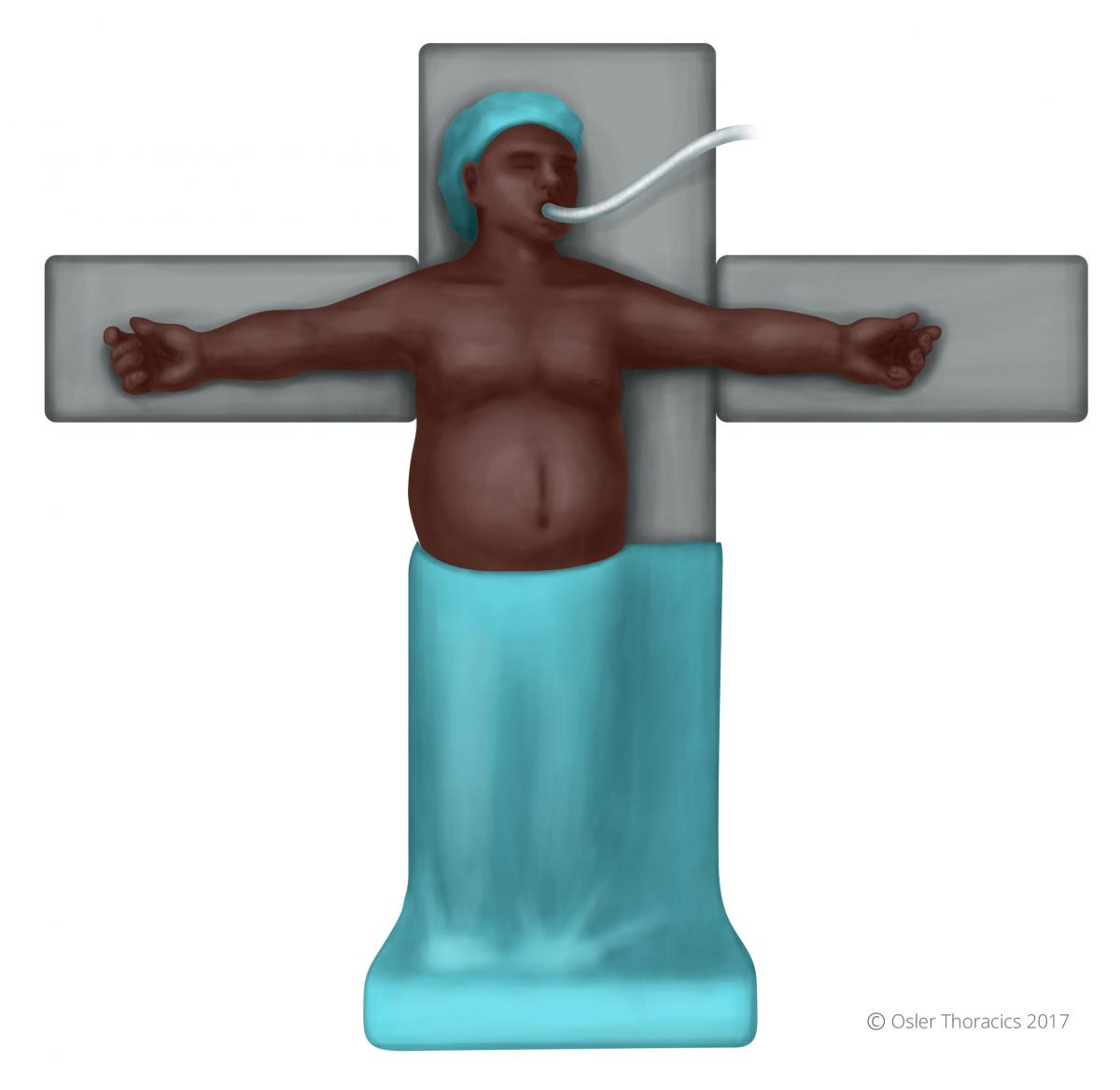

Step 1:Position of the Patient

Figure 1: Patient positioning

The patient lies supine on the bed with a foot rest. This will secure the patient well especially when you require a steep reverse Trendelenburg.

The patient is placed flush to the right side of the bed. This position adds to the comfort of the operating surgeon as well as makes the liver retractor more mobile.

Step 2:Routine Endoscopy Prior to Induction Therapy and Prior to Incisions

We feel this is critical prior to beginning therapy. Most patients at Osler receive neoadjuvant chemo/radio-therapy. Even if the endoscopy was already completed by another clinician, surgical planning should occur prior to induction therapy. This pre-treatment endoscopy should be reviewed immediately prior to surgery and should guide the extent of resection.

Many patients have a remarkable response to treatment, and an endoscopy at the time of surgery may appear normal. Despite a potentially normal endoscopy, pathology will almost certainly reveal residual disease. We also perform on-table endoscopy to provide feedback to the patient about their response to induction therapy.

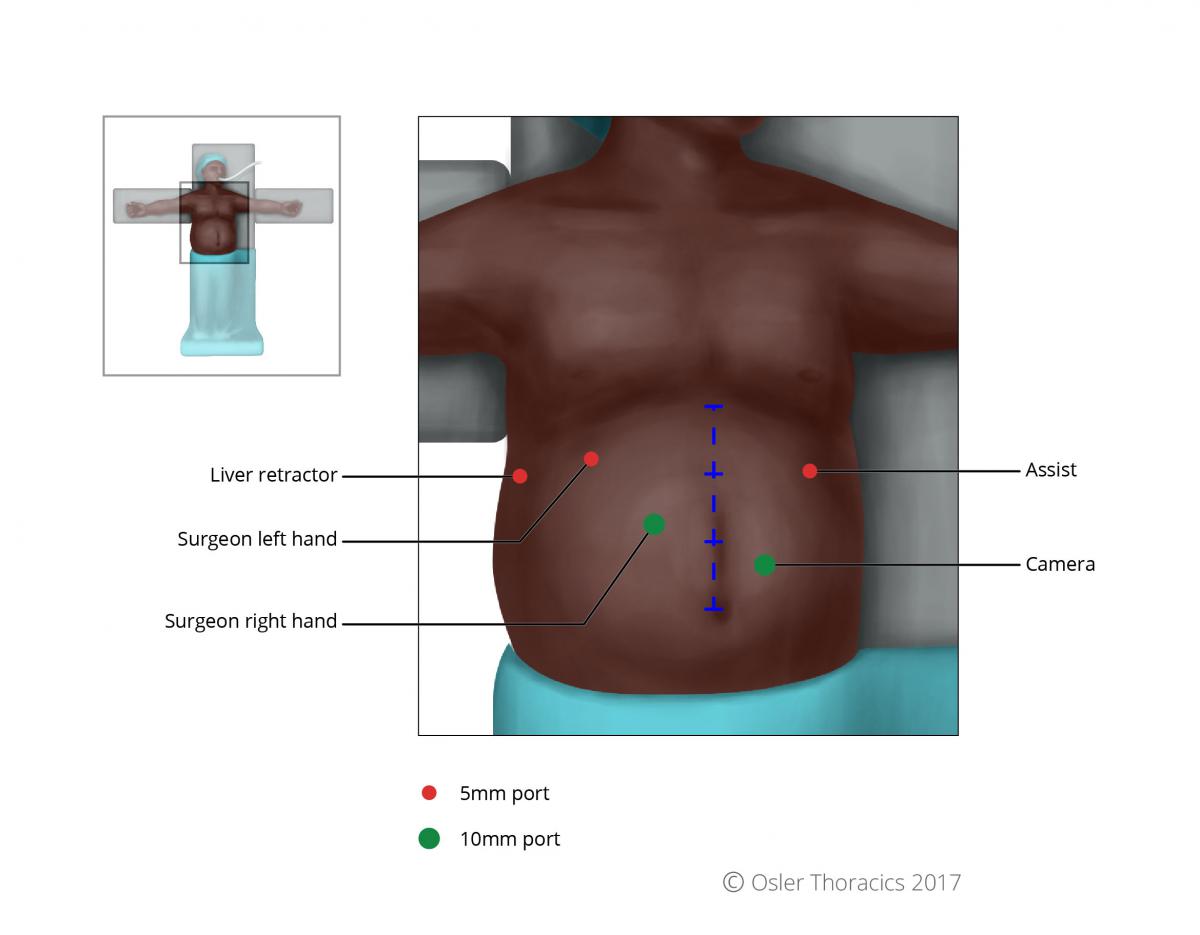

Step 3:Port Placement

Pearl #1: The Rule of Thirds

Figure 2: Port placement

Mark the patient:

- Subcostal margin, xiphoid, falciform

- Mark a line from the xiphoid to umbilicus, divided it in three

- Camera: 2 fingerbreadths below mark 2

- Working right of surgeon: at mark 2

- Remainder of ports are the same as with the Nissen Fundoplication

- RLQ Port: We call this the feeding tube and conduit port—it will allow you to suture your feeding tube to the abdominal wall and also help you maintain a straight conduit (See Pearl #6)

Step 4:Laparoscopic Staging

The advantage of a minimally invasive approach is the ability to carefully assess the peritoneal cavity prior to resection with minimal trauma to the body. We will spend a few minutes examining the liver, omentum, and abdominal wall prior to resection. Any suspicious lesions are biopsied and sent for frozen sections. This prevents futile resections in those with unsuspected metastatic disease.

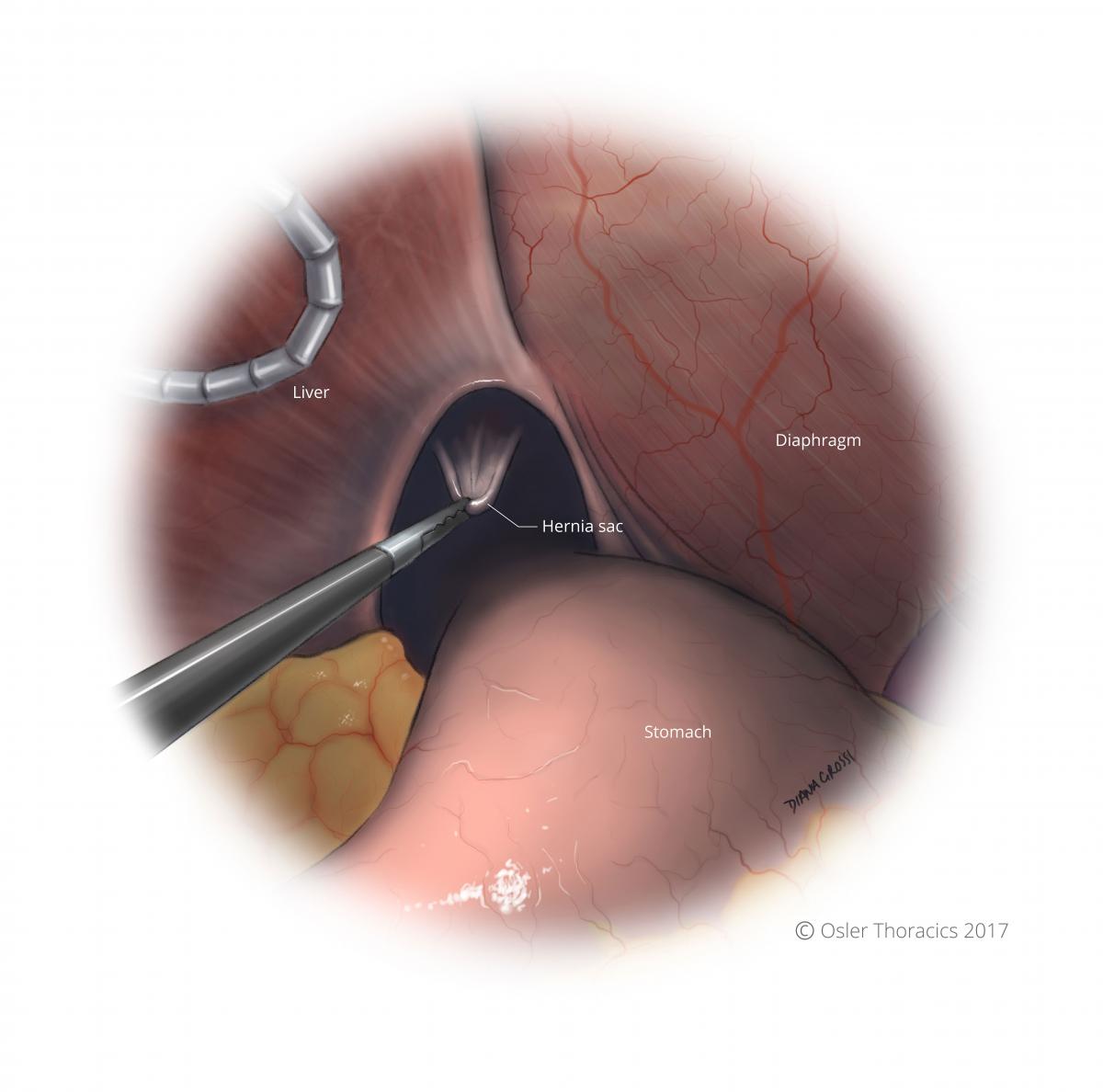

Step 5:Hiatal Dissection

Pearl #2: Reduce the Hiatus Hernia

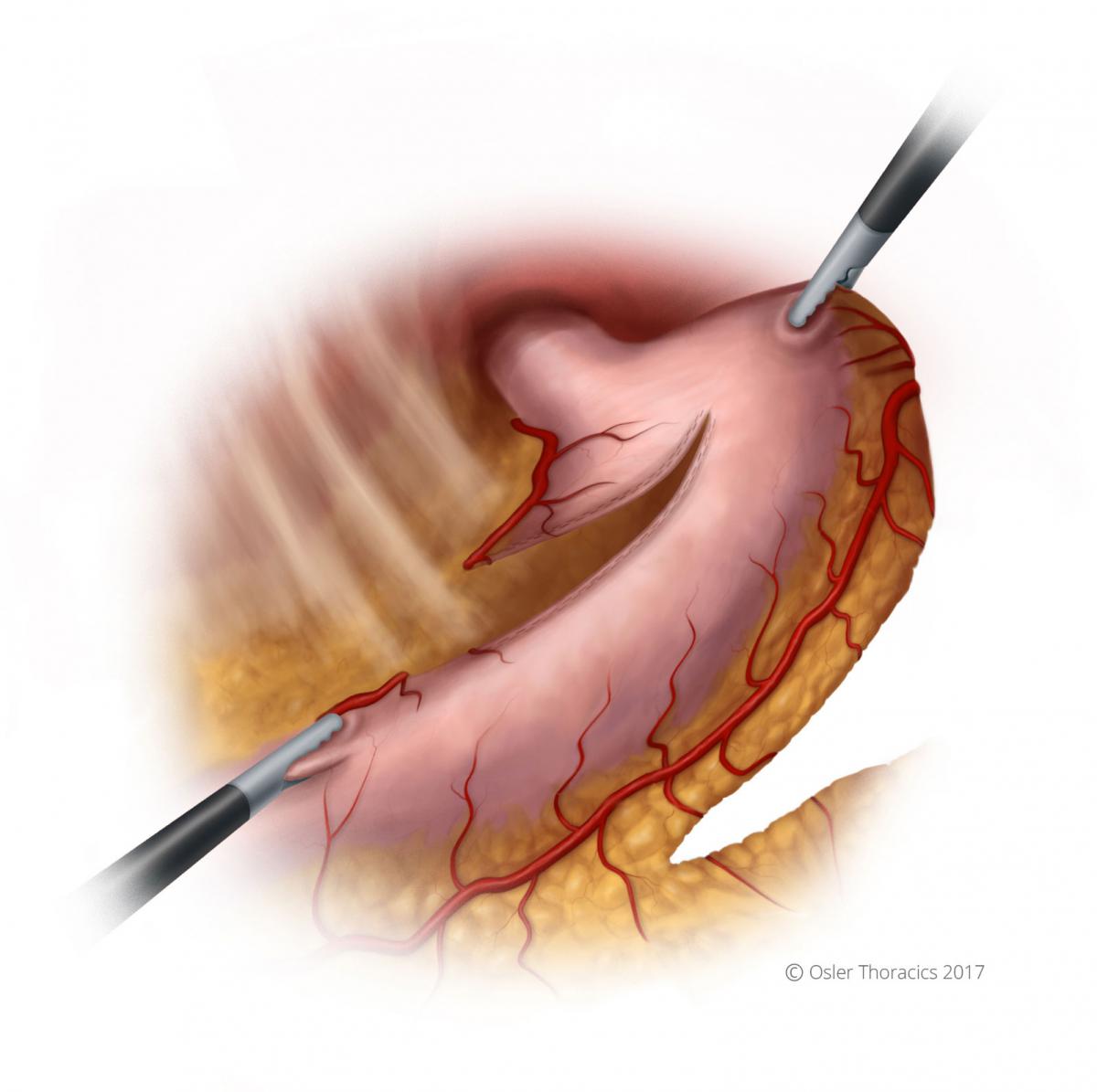

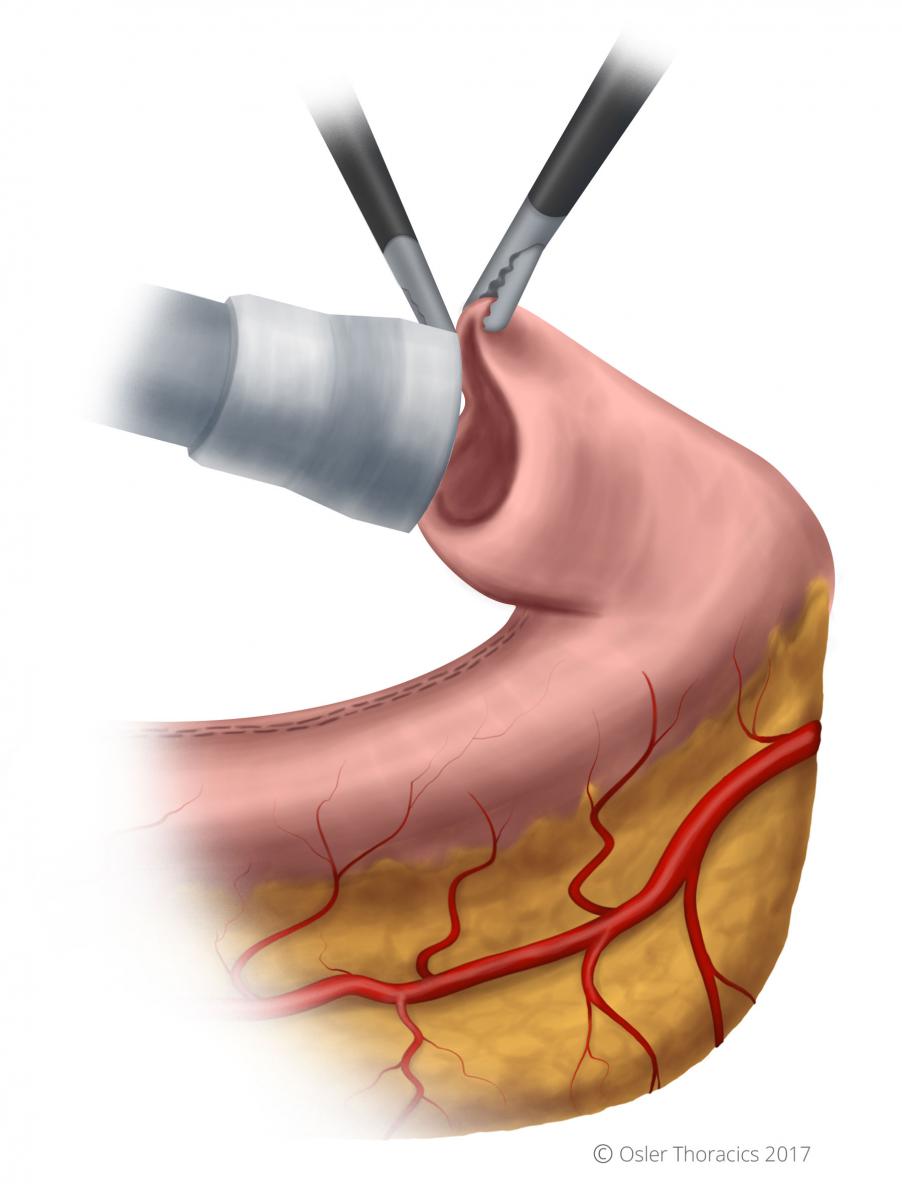

Figure 3: Grasp hernia sac and begin to pull down and evert it into abdomen

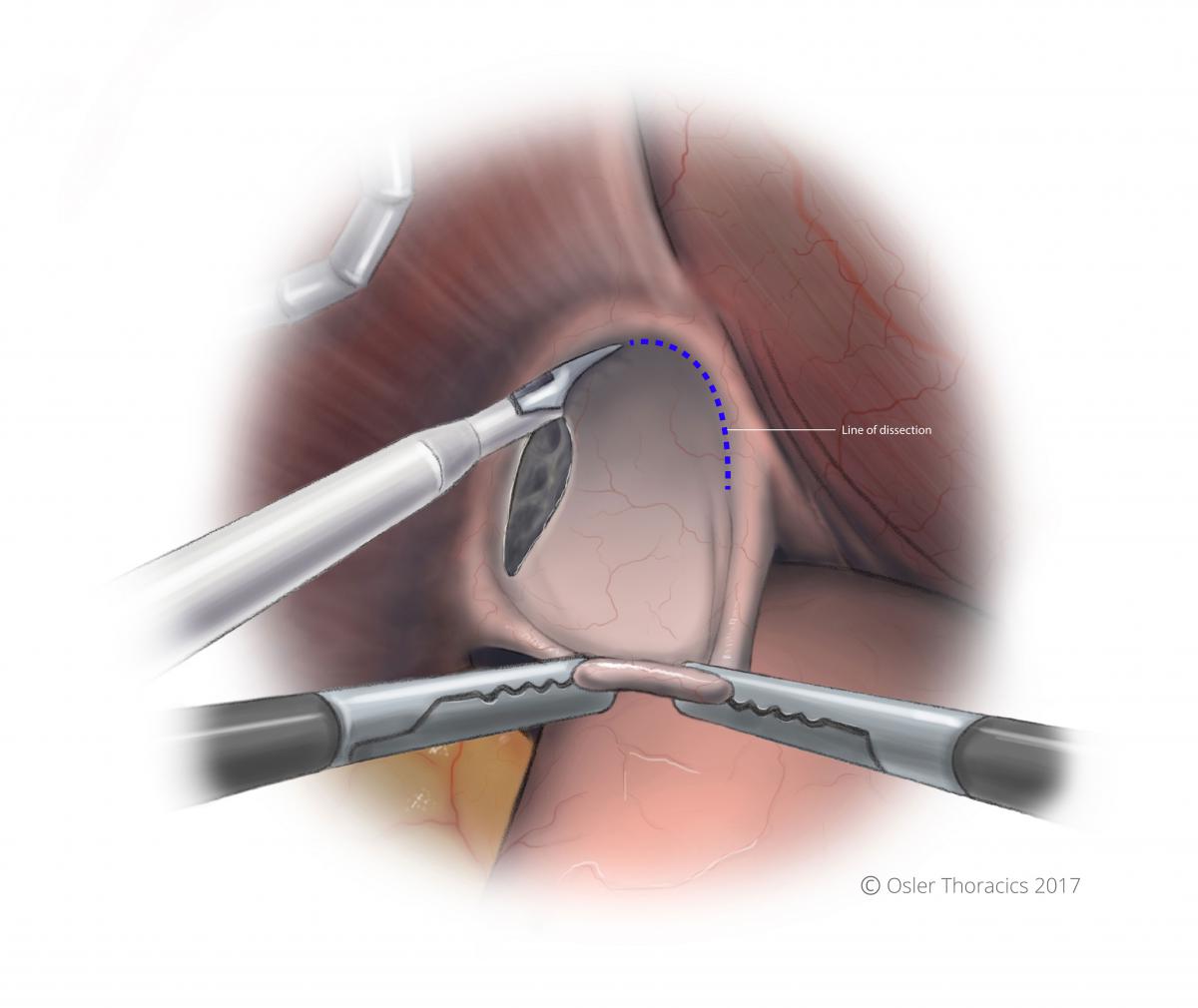

Figure 4: Evert sac into abdomen, and create a horizontal plane of dissection in the avascular plane between the hernia sac and pericardium

Figure 5: Use two-point grasping to 'roll' the sac down into the abdomen

Figure 6: Descended hernia sac with exposed anterior vagus nerve and GEJ fat pad

We begin our dissection like we do in patients with a hiatus hernia. As the most common cause of esophageal cancer is chronic GERD, it is not surprising that many patients have hiatal hernias. Using the “Anterior Sac Approach” we reduce the stomach. This will allow us to use more of the stomach to create the conduit.

Click here for a full description of the ‘Anterior Sac Approach’

Tip #1: After the hiatus is reduced we mobilize the Angle of His Fibers. Like all foregut procedures, this makes short gastric mobilization easier as it allows for more mobility of the stomach and improved exposure of the vessels.

Tip #2: We perform minimal esophageal dissection at this time. As many patients have had radiation treatment, the dissection planes between the periesophageal tissue and the pleura are often obliterated. Inadvertent pleurotomies will result in a floppy diaphragm which can be very bothersome for the rest of the procedure. Cardiorespiratory compromise may also necessitate a reduction in insufflation pressures, which will force the surgeon to complete the abdominal phase using sub-optimal exposure.

Step 6:Mobilization of the Stomach

Pearl #3: Mobilization with Minimal Grasping of the Stomach

Grasping trauma to the stomach is a common criticism of the MIE. During an open esophagectomy, the stomach is frequently manipulated by the hand, minimizing iatrogenic trauma. Without this luxury, overly aggressive grasper manipulation can lead to a “beaten-up” conduit with significant micro-vascular trauma. This may lead to leak and/or vascular ischemia.

To avoid this, we prefer to use a “minimal touch” technique to completely mobilize the stomach:

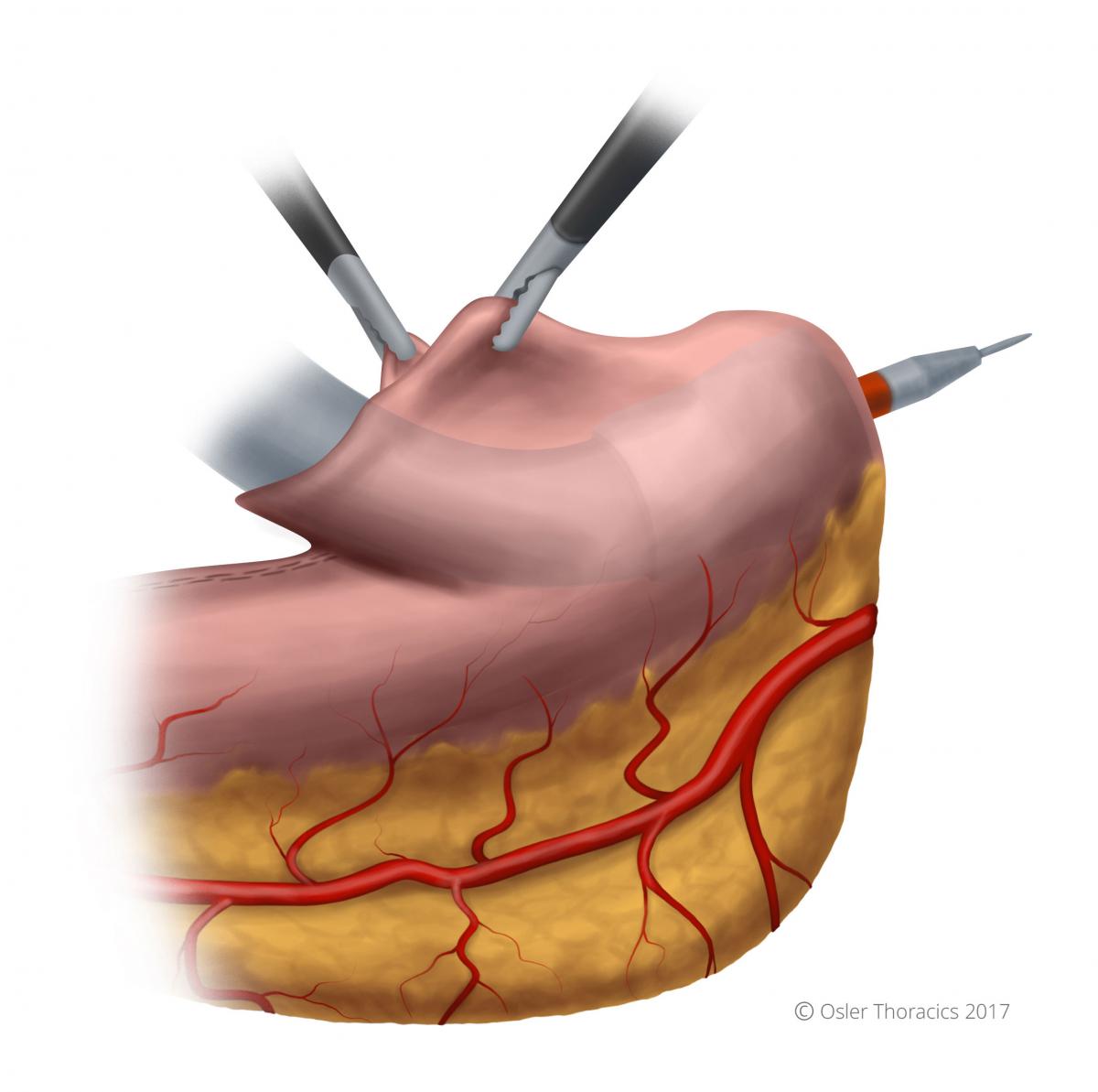

Pearl #4: Minimal Gastric Manipulation During Gastric Mobilization and Creation of Omental Flap

Although grasping the conduit cannot be completely avoided, minimizing this can be achieved using a few simple pearls:

- Entering the lesser sac by two-point grasping of the omental branches of the gastro-epiploic artery. By lifting one of these vessels with your left hand and the assistant’s hand, you can ensure you are away from the main trunk. By transecting 1-2 of these vessels you can easily enter the lesser sac safely.

Figure 7: Lesser sac revealed

- Marching up the greater curve using the omental vessels as a guide: This keeps you away from the epiploic, and also allows you to create a nice omental flap for anastomotic coverage.

- The omental flap extends from the halfway point of the gastrocolic omentum to the short gastrics. It allows you to cover the conduit staple line and the anastomosis. Obviously it is critical to avoid the colon wall during this dissection.

- As you mobilize the greater curvature, the surgeon and the assist will maintain exposure by gently grasping the omentum well away from the epiploic artery. We minimize any grasping of the stomach.

- As we approach the Ange of His, we can grab the apex of the stomach to complete the mobilization.

- All retrogastric adhesions are transected.

Figure 8: Omental flap created

Step 7:The Left Gastric Artery(LGA)

Pearl #5: The LGA Post

Prior to dissecting the LGA, it is important to clear the right crus off the esophagus. This will allow you to encircle the artery more easily.

Once this is done, using your left hand to lift the lesser curve of the stomach anteriorly, 2-3 cm distal to the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ). This is almost always demonstrates the contour of the LGA. The actual vessels may not be visible, however, the peritoneum, nodes, and fatty tissue around the artery will be appreciable.

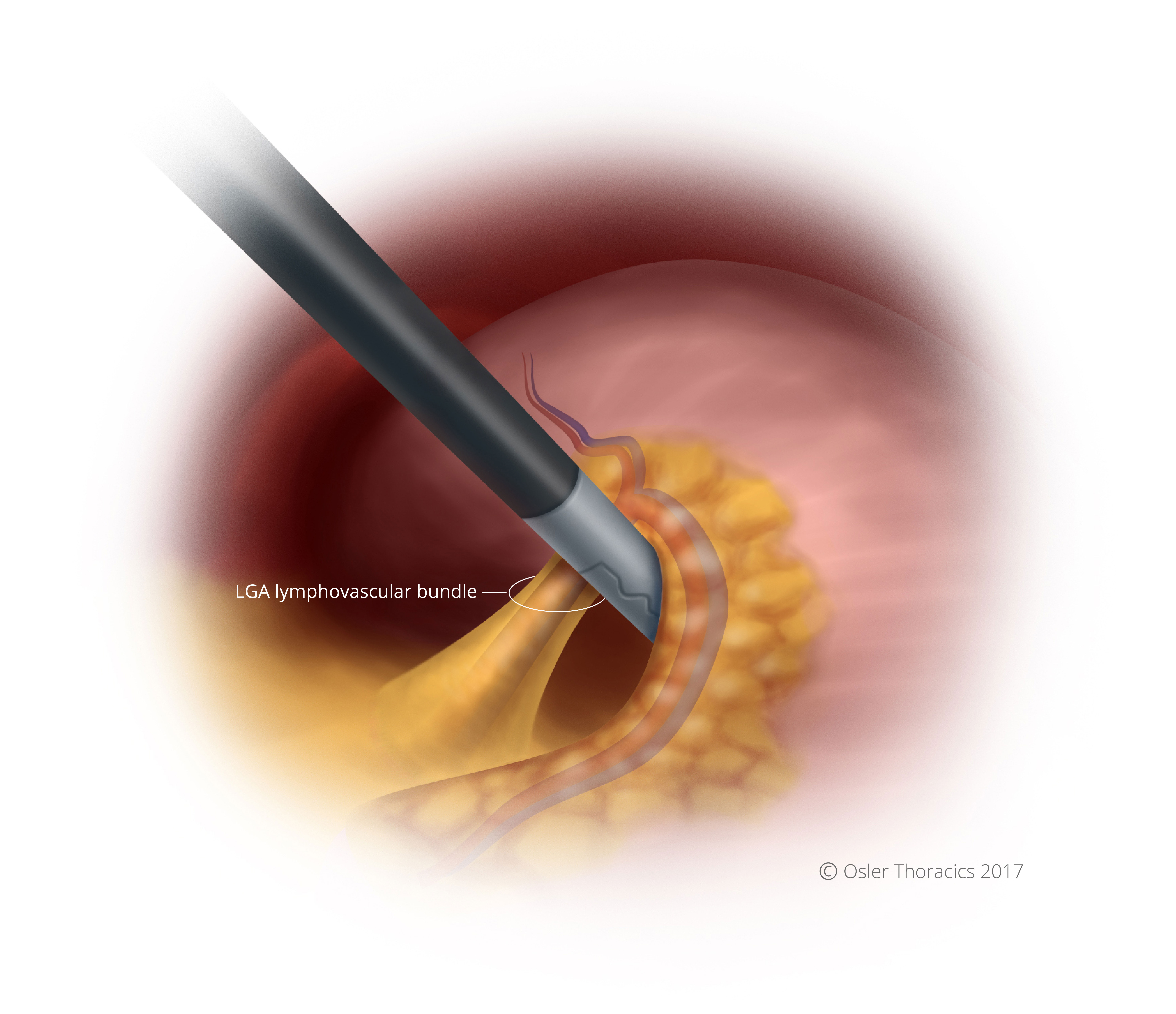

Figure 9: With the stomach lifted anteriorly, the LGA lymphovascular bundle is visible

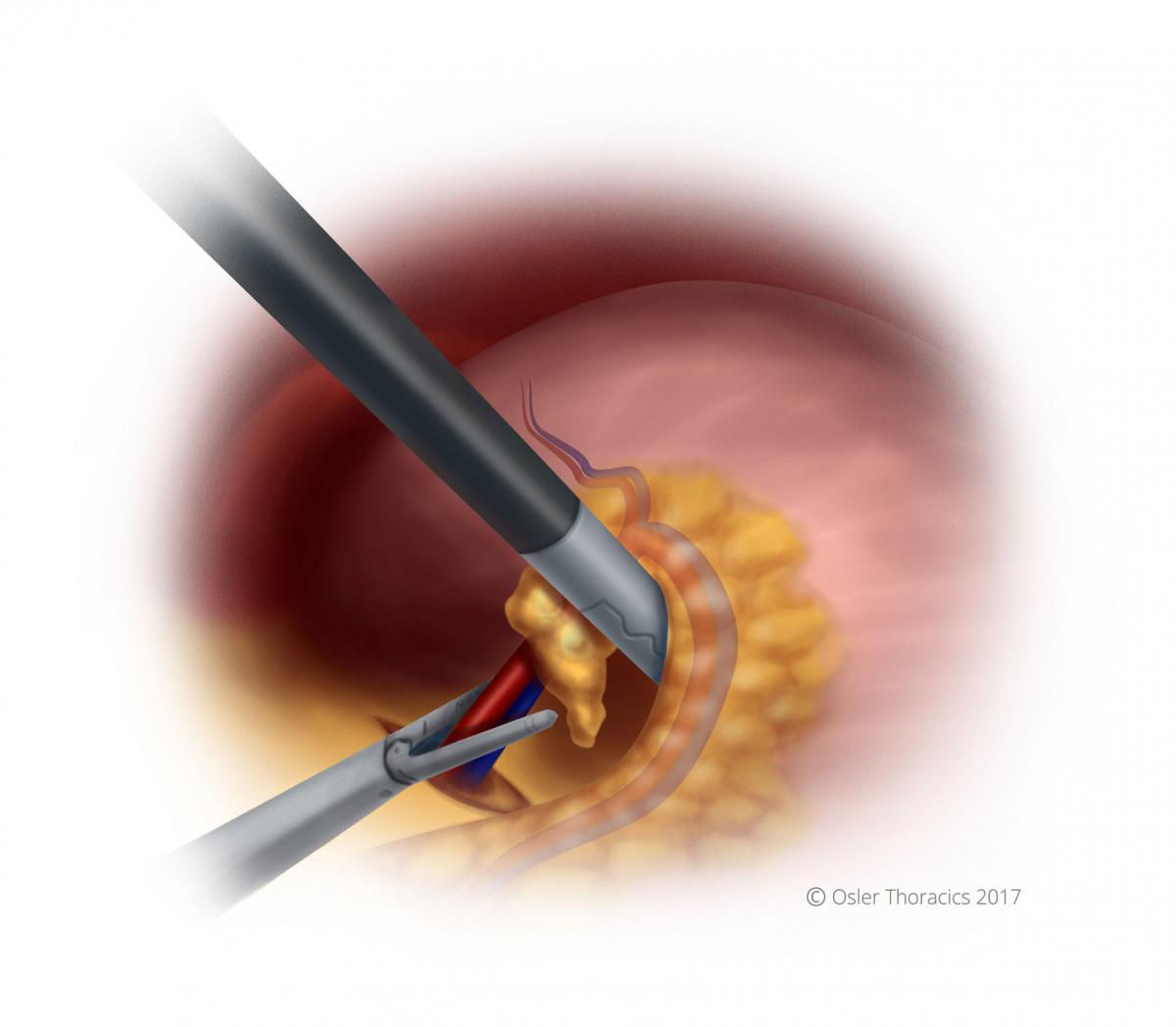

Once we have posted the LGA lymphovascular bundle, we score the peritoneum at the base and sweep all the tissue anteriorly. This will create a nice tunnel for your vascular stapler, along the base of the vessel, below the lymph nodes, and underneath the esophagus. This avoids individual dissection of the nodes and allows for a nice en-block resection

Figure 10: Stapling the LGA lymphovascular bundle

Step 8:The Conduit

Pearl #6: THE RLQ port

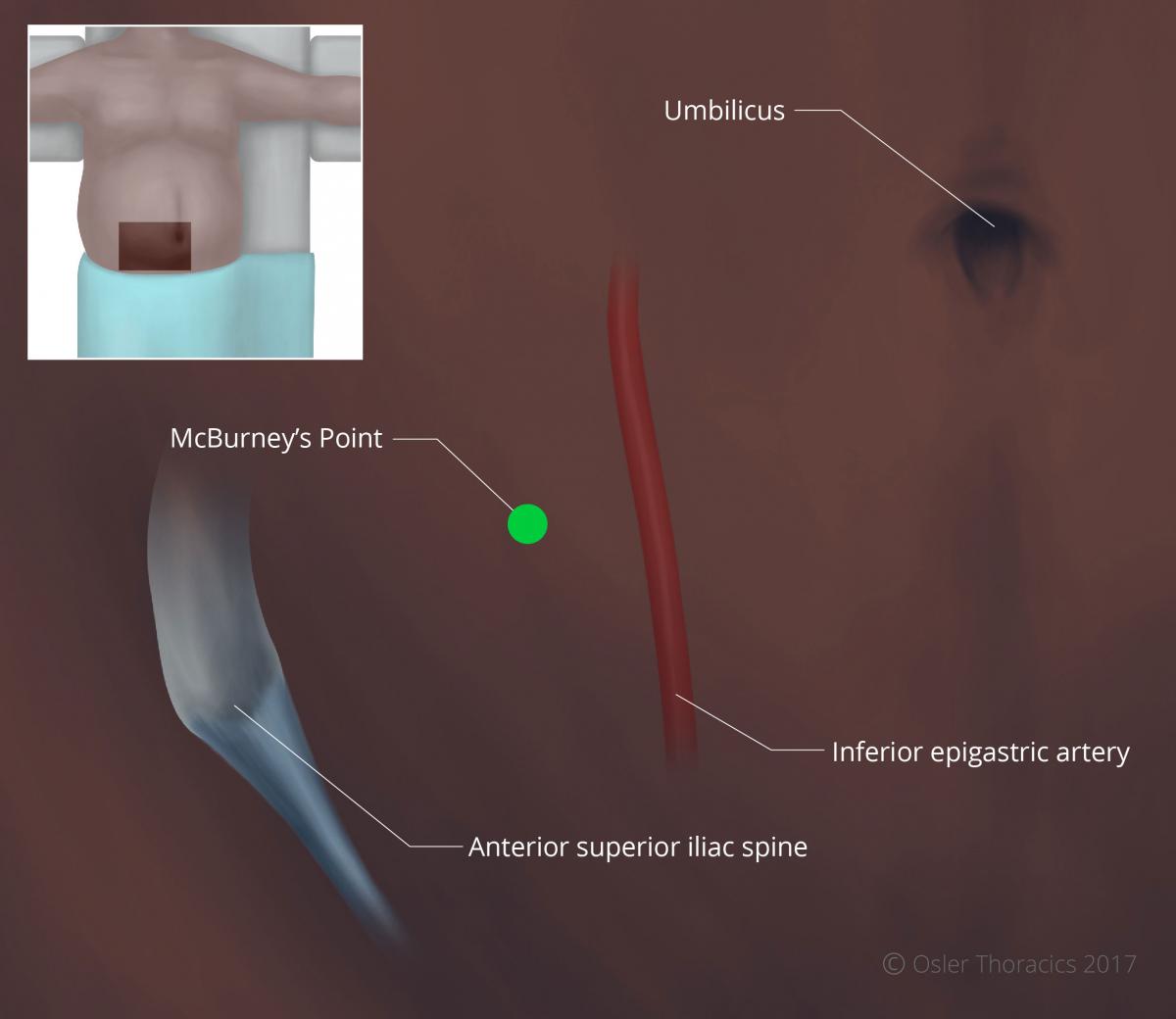

- The RLQ is needed for the feeding tube, however it is of critical importance for the creation of the gastric conduit because of the downward traction that it provides. The port is placed at McBurney’s point, making sure to avoid the inferior epigastric artery.

Figure 11: McBurney's point located two thirds the distance between the umbilicus and ASIS, lateral to the inferior epigastric

Pearl #7: Ensure Entire Stomach is Mobilized Prior to Stapling

Common areas that are not adequately mobilized prior to stapling include:

- Retrogastric

- LUQ/Angle of His.

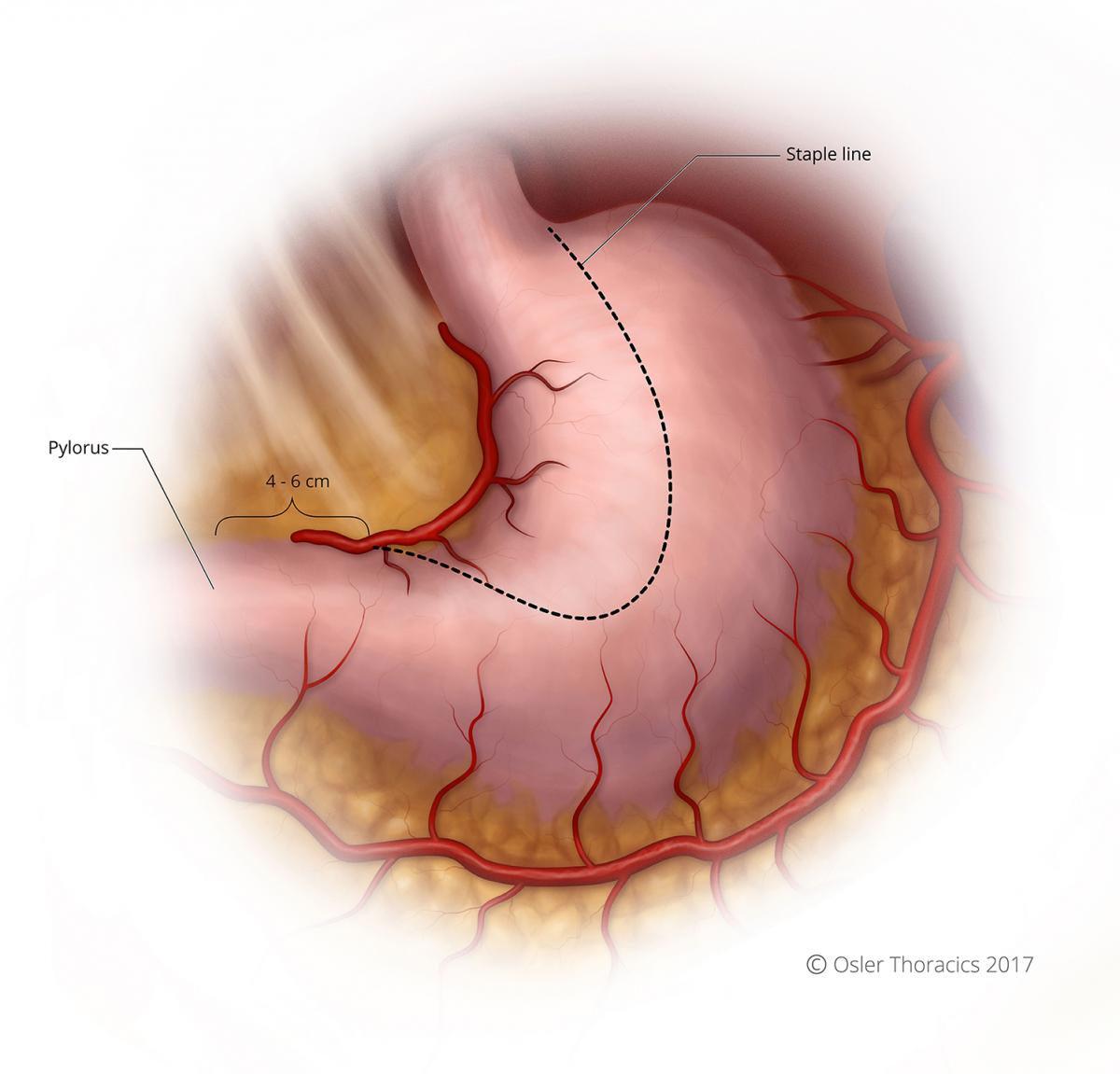

We start stapling between 4-6 cm from the pylorus. This should be adjusted based on your endoscopy. Tumors extending along the greater curvature would require you to start closer to the pylorus.

Pearl #8: Consider Using a Green Ethicon (Thick Tissue) Load on the First Staple Firing Along the Lesser Curve

This may prevent dehiscence in a typically thick area of the stomach.

Run the staple line parallel to the lesser curvature, maintaining a conduit between 3-4 cm in maximal diameter.

Figure 12: Course of staple line for conduit creation

Pearl #9: The Conduit Stretch

After your second gastric firing for the conduit, it is common for the stomach to start folding in on itself and the stapling angles to be challenging. Creating a nice straight staple line is important for its integrity and length

Figure 13: The LUQ pull, conduit stretch

The assist in handed the apex of the stomach and pulls towards the LUQ.

The scrub nurse or second assist gently grasps the staple line and pulls towards the RLQ (using the RLQ port).

As you staple, reposition the stomach to ensure the stomach is not folding within the stapler.

Completely detach the stomach. Some have advocated leaving a small bridge of tissue to maintain continuity. By detaching the stomach, you allow for better exposure of the esophagus as you mobilize laparoscopically.

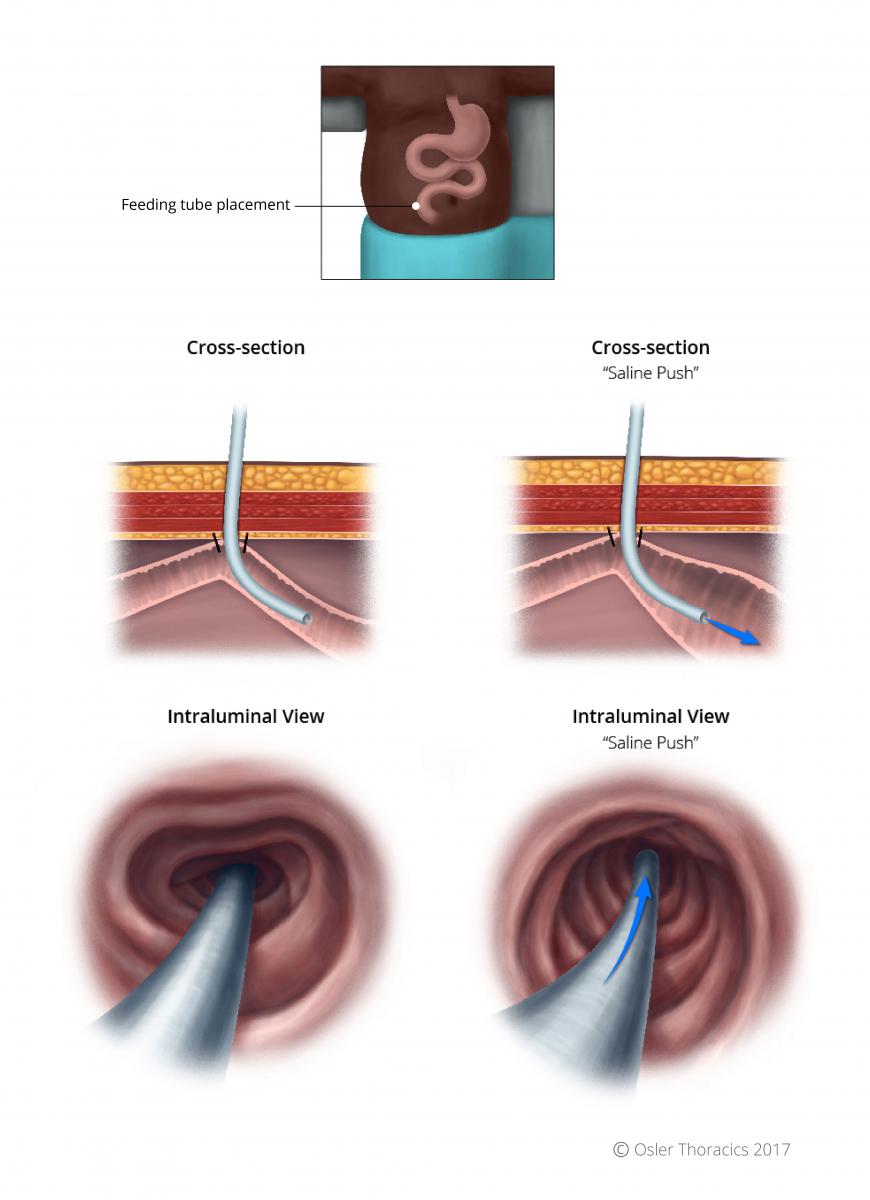

Step 9:The Feeding Tube

We always place a feeding tube. Feedings are slowly begun 24hrs after surgery. We use the “percutaneous Barone set” and the Endo-Stitch to place the feeding tube 20 cm distal to the Ligament of Treitz.

Tip#1: Place 2ND stitch left lateral while reflecting the small bowel to the right.

Tip#2: One bite abdominal wall, to bites on the small bowel. This ensures that the tube is completely surrounded by bowel wall.

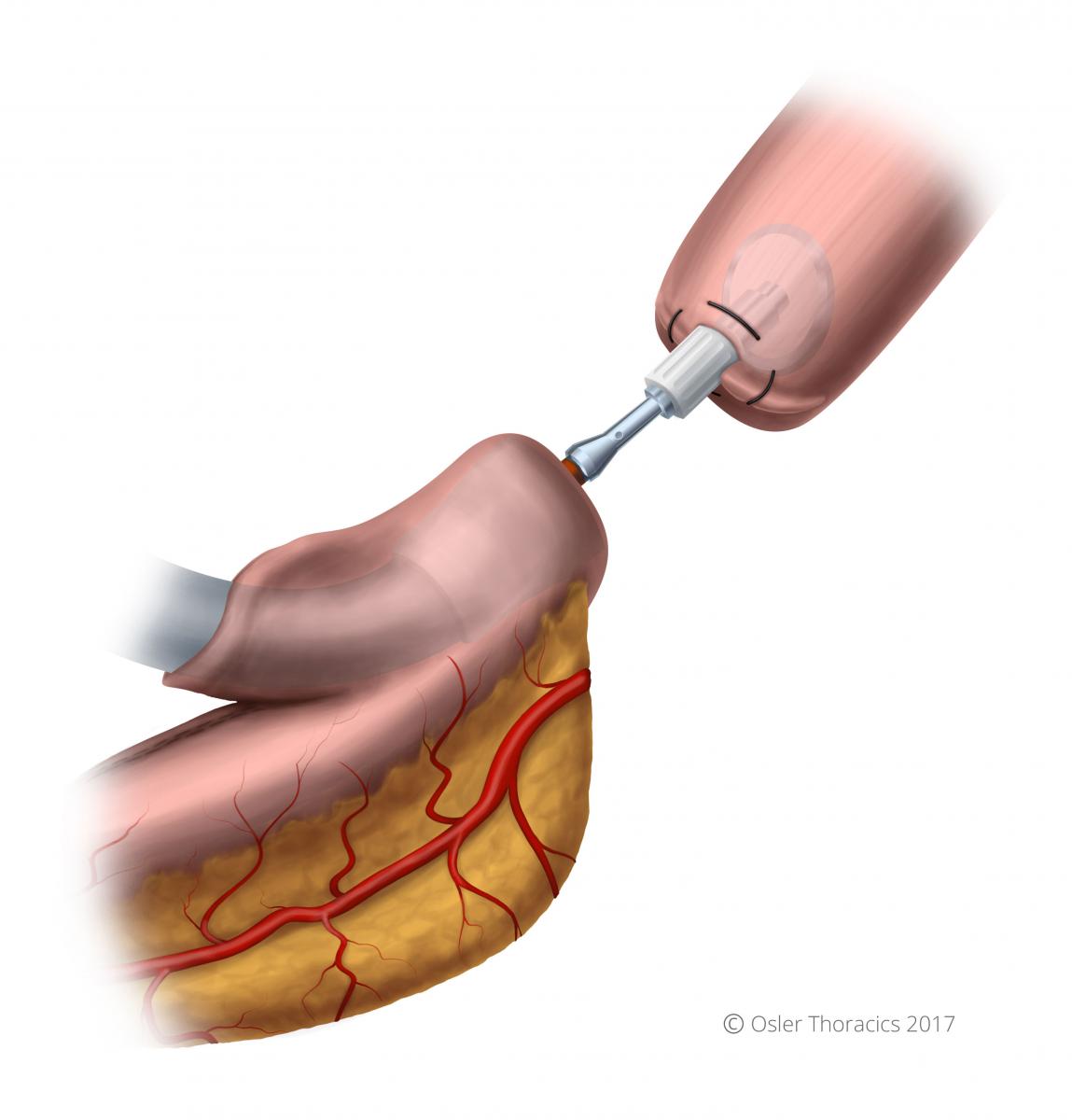

Pearl #10: Feeding Tube Saline Push

It can be occasionally challenging to thread the feeding tube distally. Once the feeding tube in inserted into the lumen it is only advanced 4-5 cm. The guidewire and inner cannula are then removed. A 60 cc syringe filled with saline is attached to the feeding tube. You assist pushed the saline through as advance the feeding tube. The saline creates a stream of saline that will distend the stomach full the tip of the tube off the small bowel wall as it is guided through.

Figure 14: Cross-sectional view of the feeding tube into the small bowel; the saline push facilitates the tube’s advancement

Step 10:Mediastinal Esophageal Dissection

Pearl #11: Perform Extensive Mediastinal Esophageal Dissection Prior to Turning Patient

Prior to turning the patient, and tacking the conduit, we strongly recommend extensive mediastinal dissection. The exposure through the hiatus is usually excellent, and the distal esophagus can often be mobilized safely to the inferior pulmonary vein.

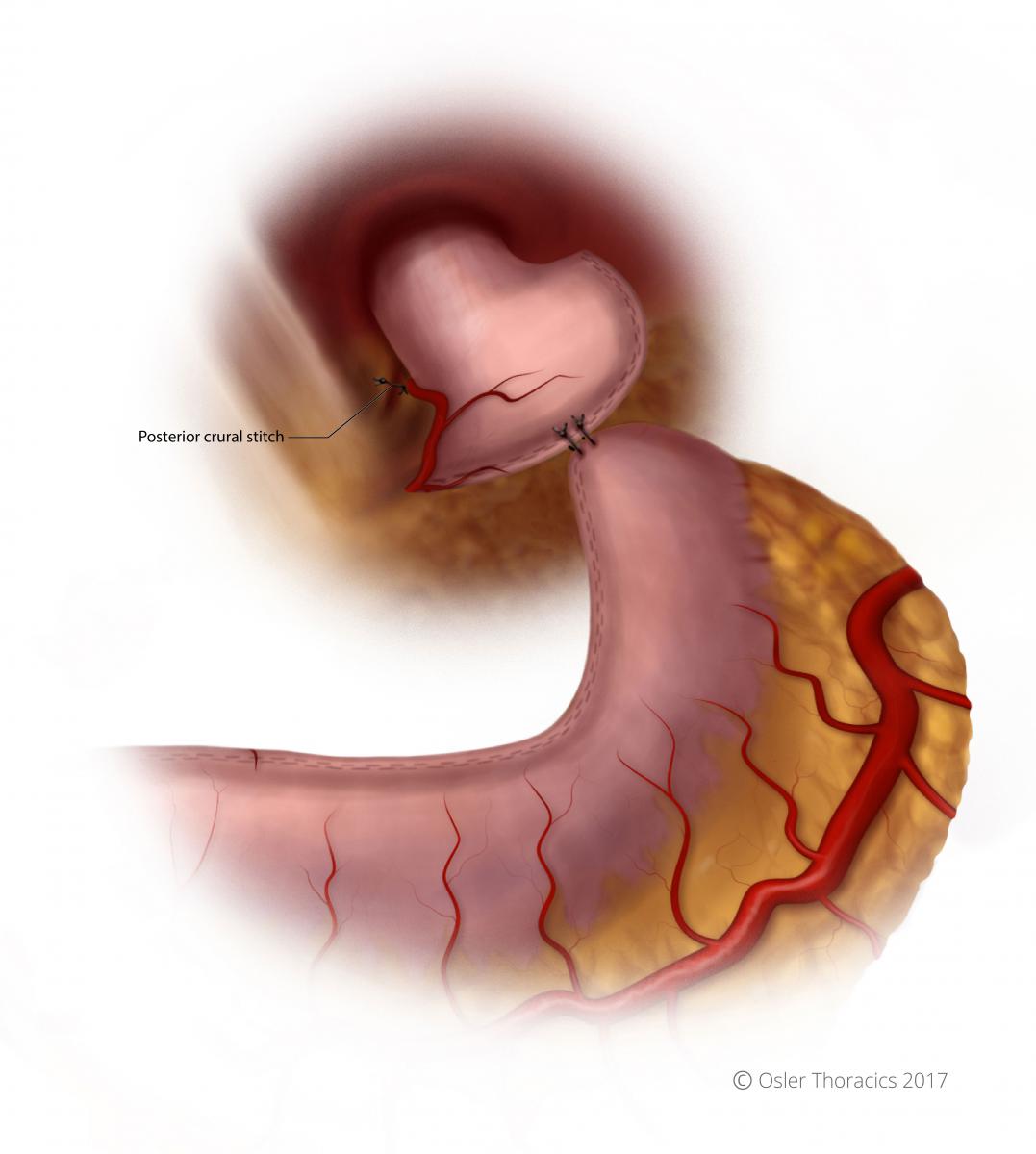

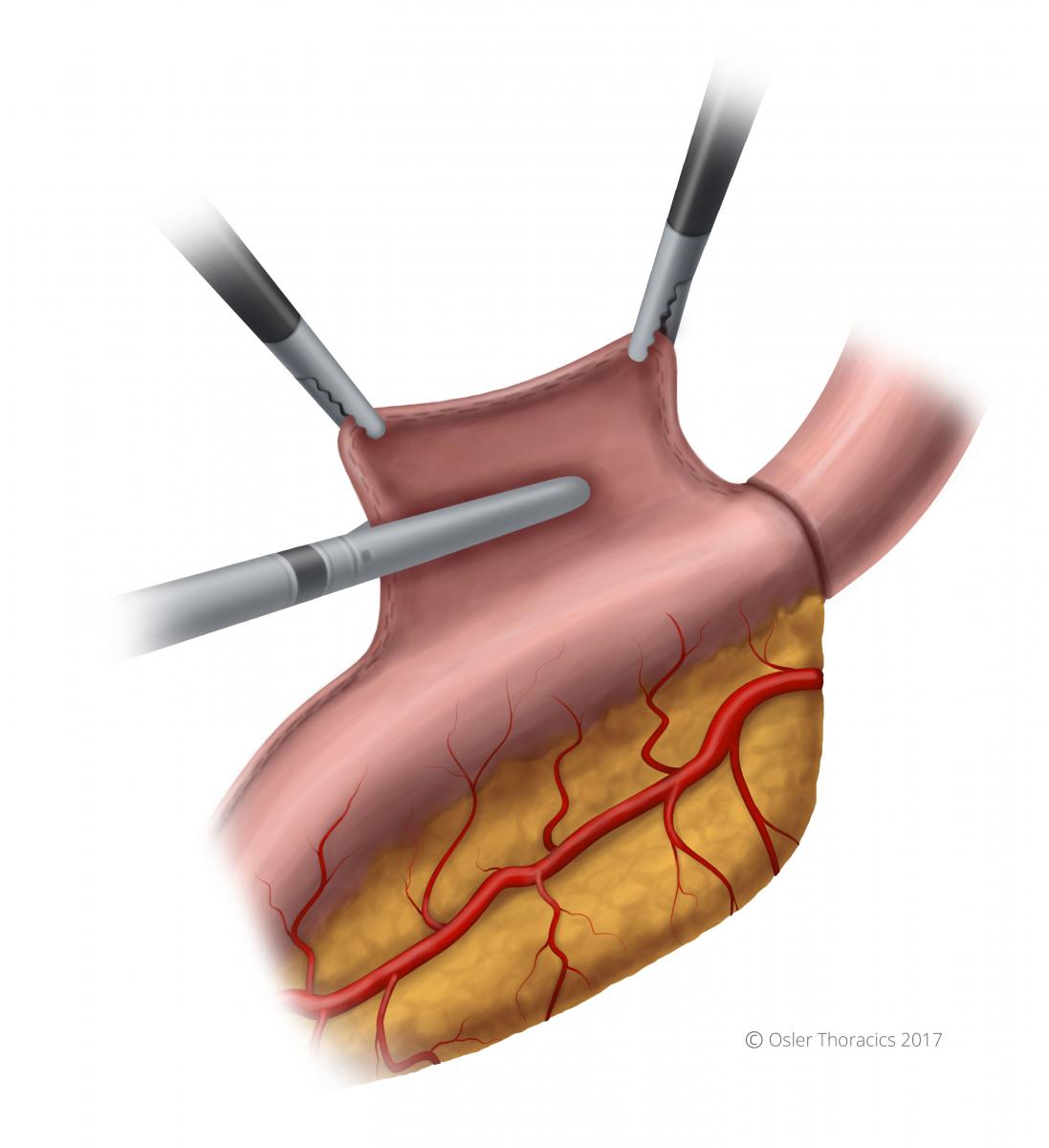

Pearl #12: Two-Point Tacking to Recreate Normal Anatomy

To prevent a twisting of the conduit as it is pulled up into the right hemithorax, we suture the conduit to the specimen at two spots, 1 cm apart.

Step 11:The Posterior Crural Stitch

Pearl #13: Posterior Crural Stitch

We have seen a 2 of our long-term survivors return to us complaining of systems suggestive of conduit compression. Imaging revealed transverse colon herniation through a gaping hiatus.

Although this Is easy to fix laparoscopically, in patients with a large hiatus, we routinely place a posterior crural stitch. It should be snug enough to prevent herniation, but lose enough to allow for smooth delivery of the conduit into the chest.

After the stitch is complete we tuck the conduit into the mediastinum.

Figure 15: Conduit stitched to specimen; posterior crural stitch visible

Thoracoscopic Steps

Thoracoscopic Steps

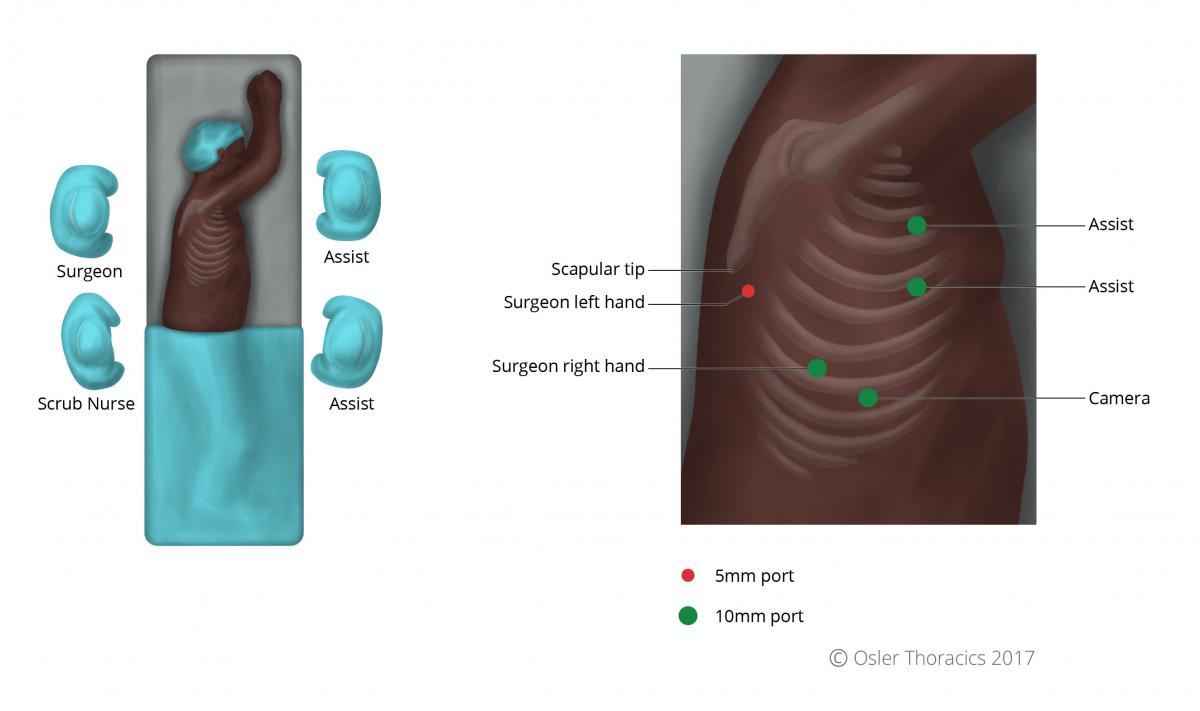

Step 1:Port Placement and Exposure with Two Assistants

The VATS part of an MIE is best completed with the help of a second assist who has two ports. This allows the cameraman to focus on maintaining excellent exposure and another assist who provides retraction.

Figure 16: Patient and surgeon position for the VATS portion of the procedure

Like an open Ivor-Lewis Esophagectomy, the patient is turned to the left lateral decubitus position. The two assistants stand to the left of the bed, while the surgeon and scrub nurse are on the right.

We use 5 ports:

- Camera: 10-mm port in the 9th intercostal space along the anterior axillary line. Placing it too posteriorly will results in it being too “in-line” with the surgeon’s right working port, while placing it too anteriorly will result in a mirror image.

- 10-mm surgeon-right working port is usually placed in the 8th intercostal space approximately 5-7 cm posterior to the cameral port.

- We place two 10 mm assist ports anteriorly in the 4th and 6th interspace, for a fan retractor and a suction device. As the initial dissection is in a closed system, a hand-controlled suction device is recommended to prevent negative pressure in the pleural space.

- A 5 mm port is placed posterior and inferior to the scapular tip, serving as the surgeon’s left hand.

Pearl #13: The Diaphragm Stitch

A diaphragm stitch can vastly improve your exposure in the right hemi-diaphragm.

The surgeon introduces an un-cut Endo Stitch™ into the right working port and places it into the tendinous part of the diaphragm. Using a Carter-Thompson suture grasper placed through the side of the camera port, both ends are pulled though the camera port incision (the camera and port are not removed). The retraction is maintained by placing a snap on the suture when flush to the chest wall.

Figure 17: The diaphragm stitch

Step 2:Esophageal Mobilization

The inferior pulmonary ligament is incised to the inferior pulmonary vein.

The mediastinal pleura is divided along the hemi-azygous vein. Once the azygous is reached, it is encircled and stapled. The esophagus is pulled laterally by the assist’s right hand.

Dissection is carried out along the pericardium, with the surgeon pulling the esophagus posteriorly.

The pericardial dissection is where the airway must be carefully preserved. The dissection occurs under the airway, along the bronchus intermedius and carina. The subcarinal nodes can be mobilized and resected.

Figure 18: The inferior pulmonary ligament incised, and esophagus mobilized to level of the arch of the azygous

Pearl #14: Avoid Energy Near the Airway

The harmonic scalpel can easily result in injury to the membranous portion of the airway, either from direct injury or from thermal spread. The subcarinal space can be very vascular, so sometimes it is hard to avoid its use. We use blunt dissection in this area, however we use precise application of energy when a feeding vessel is identified. The nodes are cleared, demonstrating the skeletonized subcarinal space.

Figure 19: Skeletonized subcarinal nodes visible

The hemiazygous dissection is carried out while the assist pulls the esophagus anteriorly.

Pearl #15: Liberal Use of Clips to Avoid Bleeding and Lymphatic Leaks

We avoid the thoracic duct, but ligate it if we are concerned about its integrity. Although the harmonic scalpel can control the aortoesophgeal vessels well, the accompanying lymphatics can result in small but frustrating chyle leaks. By placing clips, this can be avoided as we do not feel small lymphatic vessels can be adequately sealed with energy.

Pearl #16: Early Pull-Up of Gastric Conduit

After the lower part of the esophagus is completely mobilized approximately 5 cm above the hiatus, we routinely pull up the conduit. This results in significantly improved mobility and exposure, making the rest of the dissection very easy.

We do not pull up too much conduit immediately, preventing crowding. The mobilization of the esophagus is carried up to the level of the azygous vein.

Figure 20: Conduit and specimen pulled into chest

Step 3:Transection of the Esophagus and Preparation for the Anastomosis

Depending on the location of the cancer the assistant staples the esophagus from the anterior port.

Figure 21: Esophagus transected with stapler

Figure 22: Blind ends of esophagus and specimen

Step 4:Removal of the Specimen

Usually this is done by extending the surgeons right hand port, converting it to a 4 cm incision. A wound protector is placed.

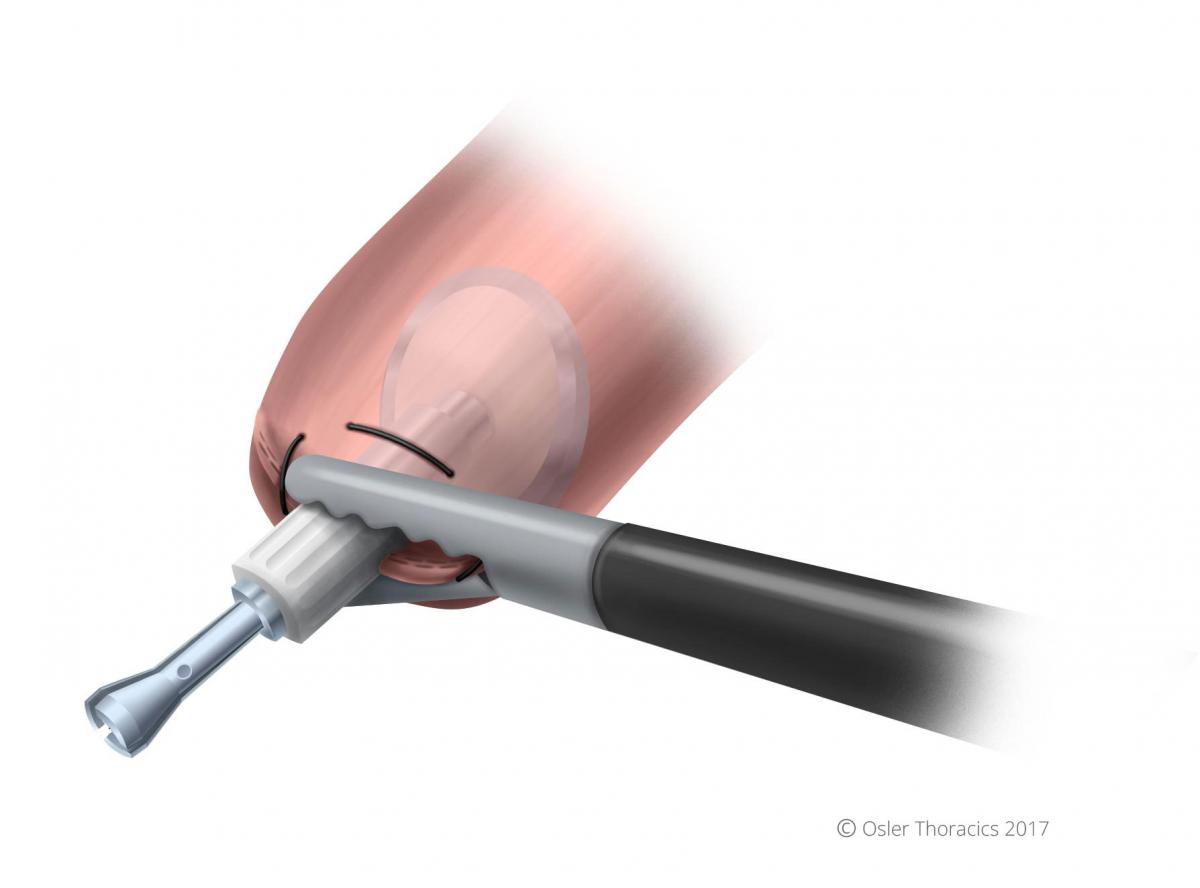

Pearl #17: The OrVil™: Eliminating the Need to Go to the Neck

In our early experience, we simply used scissors to cut the esophagus. We would place two purse string sutures around the esophagus and cinch it around the EEA anvil. This approach is time consuming, technically challenging, and limits the proximal margin because of esophageal retraction. Although it is still possible, ergonomically, it is challenging to create your anastomosis near the thoracic inlet.

With the OrVil™ stapling device, our anastomosis can easily placed high in the chest. In fact, the anastomosis is frequently at the same location of a McKeon.

The OrVil™ tube is placed in the mouth. And threaded into the esophagus where it is pulled through a small esophagotomy.

Pearl #18: Tricks with the OrVil™

- Disinfect the mouth with an antiseptic swab.

- After the assist places the orogastric (OG) part of the OrVil™ into the mouth the surgeon grabs the posterior side of the esophageal staple line, while the cameraman grasps the anterior side. A large bite is taken to obliterate the lumen and guide the tube into the centre of the staple line.

Figure 23: Hole made at tip of blind end of esophagus

- The harmonic scalpel is used to make a very small esophagostomy directly at the centre of the staple line. Using gentle pressure the assist pushes the tube through the hole.

- It is important for the assist to guide the anvil into the mouth. The concave part of the anvil should face the hard palate. Avoid getting caught on the double-lumen tube, temperature probe, etc.

Figure 24: Tube gently pushed through hole at blind end of esophagus

- The suture is cut at one place and the OG tube is removed. Gloves are changed.

Figure 25: Anvil in position in esophagus

Pearl #19: The Square Purse String

- A square purse string is placed around the anvil. This ensures that all edges are tightly secured around the anvil. After we started doing this, we noticed our EEA Donuts were more complete and our leak rate plummeted.

Figure 26: The square purse string

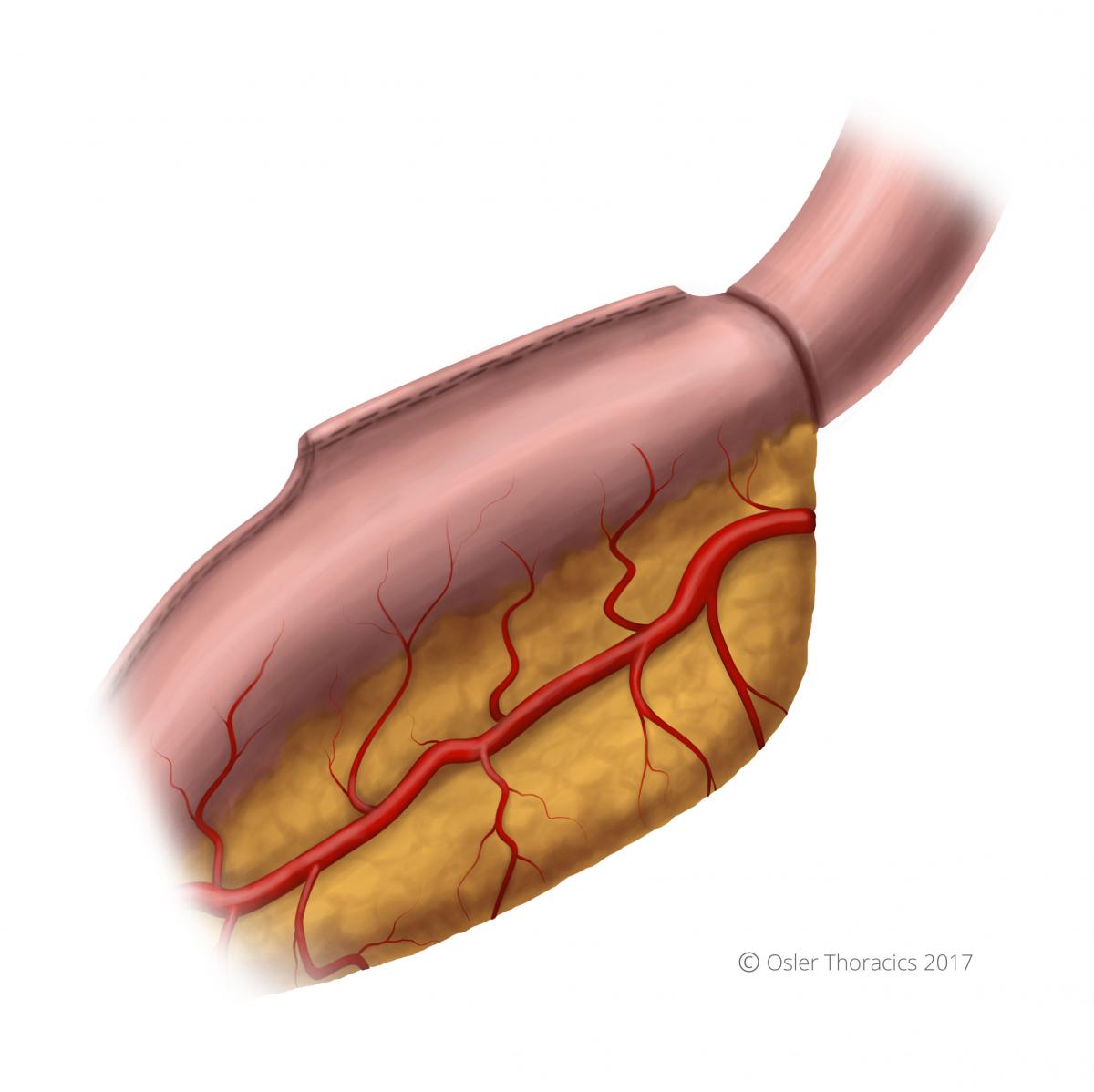

Step 5:Pull of the Stomach into the Chest

Ensure that the staple line is straight and facing laterally.

Figure 27: The stomach is pulled up into chest

Pearl #20: Avoid a Redundant Stomach

We all enthusiastically pull up the stomach and revel at its length. However, pulling up excessive stomach can lead to a very redundant conduit. Even if this is recognized, it is often difficult to tuck back into the abdomen without inflicting trauma to the conduit. The conduit is pulled up to about the carina, and the rest is pulled up during the anastomosis. This ensures that only the necessary length is used.

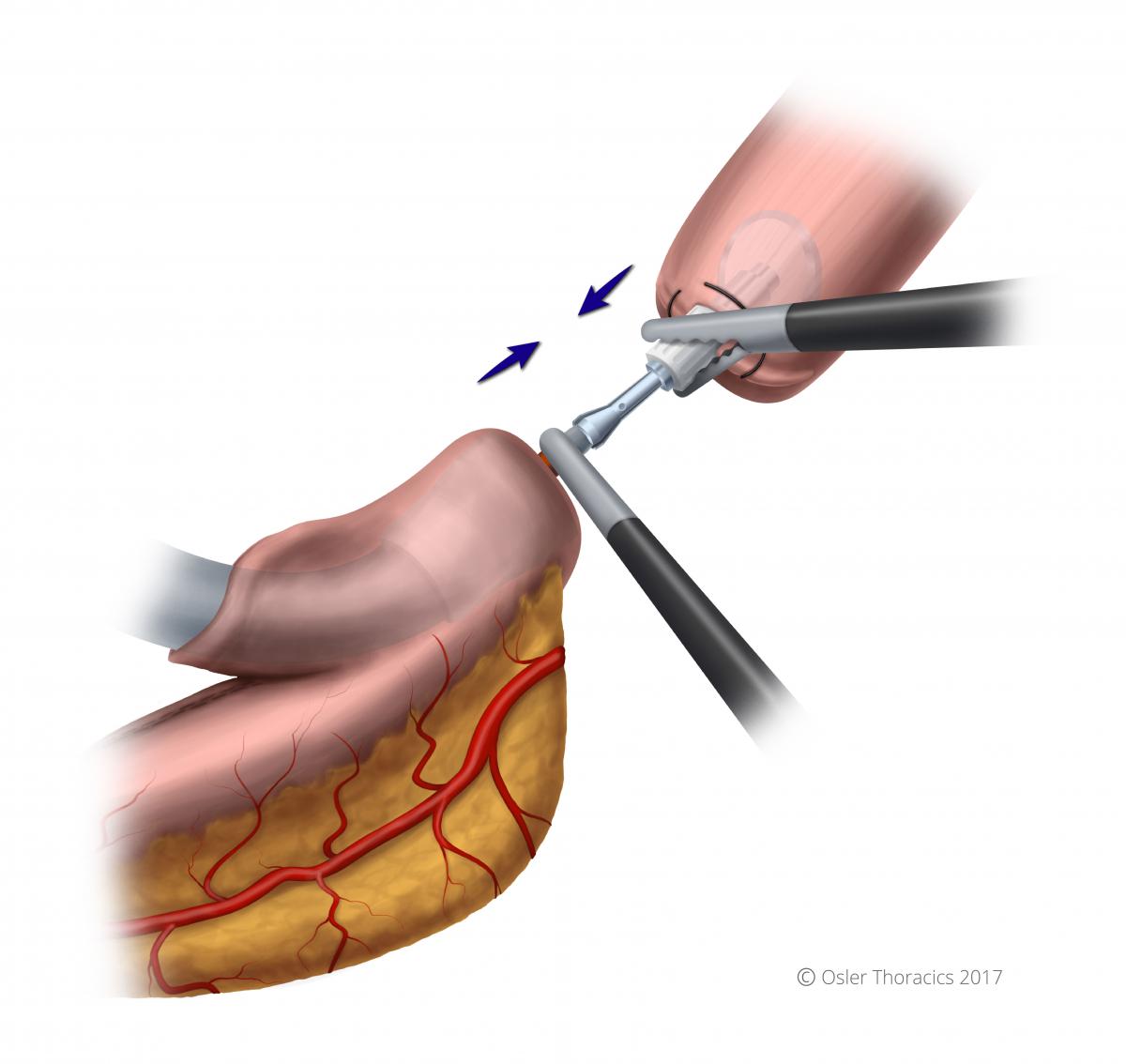

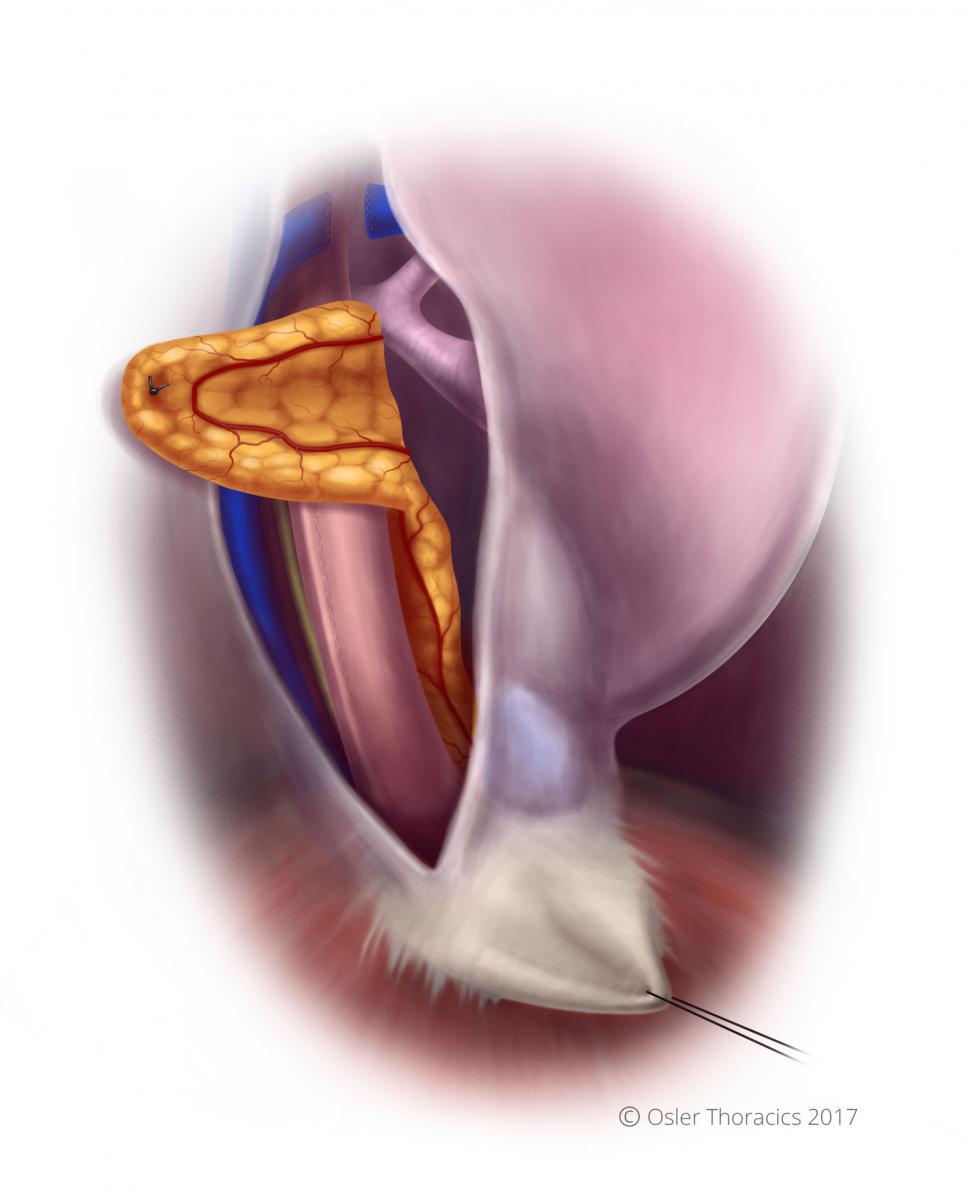

Step 6:The Foot Going into the Sock

A gastrotomy is made at the tip of the gastric tube. The stapler is passed into the gastric conduit using two graspers. The stapler passes into the conduit like a foot goes into a sock, with “the toes being the site of the anastomosis”. This will allow you to later amputate the gastric tip, which can be dusky.

Figure 28: The "foot going into the sock"

Figure 29: With the stapler in place, the needle is deployed

Once in the proper positon, the needle is deployed completely, piercing the greater curvature of the stomach. The surgeon hold the “sock” in position with his left hand while the assist grasps the anvil with a firm instrument. We use the “Swedish Debakey”.

Pearl #21: Mating the Anvil with the Stapler

Initially we struggled with this step. Two-dimensional optics prevented a seamless mating. There are a few pearls to consider when mating the anvil with the stapler:

- Use the stapler to pull up the rest of the conduit to avoid redundant stomach.

- The surgeon should maintain a left hand pull on the conduit as it lies in the stapler to prevent the needle from coming out.

- Grab the anvil by the white plastic base. This keeps the metal port open.

Figure 30: Grasping white plastic base of anvil, metal port opens

Figure 31: Mating the stapler and anvil

- Once inserted, it is clicked in my the surgeon pushing the stapler and the assist pulling the anvil. The anvil is “wiggled” into the stapler needle.

- Be aware that when pressure is applied with resistance, the needle can retract, so the camera man is asked to hole the needle dial taught during the mating process.

- Once mated ensure that the orange part of the needle is within the anvil.

Figure 32: The stapler and anvil successfully mated

- While closing the stapler, be aware that when the anvil staple line straightens there is a feeling of release that may worry you. This is normal and undoing anything to inspect is unnecessary.

- Prior to firing make sure there are no other structures in the staple line.

Step 7:Closure of the Gastrotomy

After an NG tube is placed, the gastrotomy is closed using the Echelon Stapler. The specimen is marked and sent for final gastric margins.

Figure 33: Closure of the gastrotomy

Figure 34: Completed anastomosis

Step 8:Cover Anastomosis with Omental Flap

Figure 35: Anastomosis covered with omental flap

The omental flap is used to cover the anastomosis. Suture the omental flap to the parietal pleura in a tension-free manner.